What is “Value” in a Value Proposition?

Whenever we meet a new company, one of the first questions as we get to know them is, “what’s your value proposition?” or more colloquially, “what’s your shtick?”. In Silicon Valley, the answer often launches into some techno-jargon that sounds compellingly incomprehensible, creating the probably not unreasonable feeling that it’s designed to obfuscate a lack of clarity or to bamboozle techno neophytes rather than convince a thoughtful, professional buyer. Let alone an analyst.

We’ve all had those conversations. But since pointing out what doesn’t work isn’t enough, this blog outlines one prescriptive approach to crisply and analytically correctly drill into what a convincing value proposition might be.

Let’s start with first principles? What is value? The short answer is that its incremental profits that are incurred by the buyer of your offerings. If you could have two parallel planets, and the only difference between them is that on one planet they bought your product and on the other planet they didn’t, at the end of the first year of use, the bank accounts of your buyers on the first planet should have more money in them than the non-buying users on the second planet have. The difference in the amount of money between the two groups of bank accounts is your “value add.”

So, if the value is the same as incremental profits, then the value can be defined as additional revenues plus incremental cost savings since profits are revenues minus costs. Each of those variables, in turn, can be broken down into further, logical sub-components. For example, incremental revenues might be comprised of possible price increases times potential increases in sales volumes. Or, increases in cost savings might emanate from a reduction in overhead costs or a lowering of variable expenses. With real offerings, the total value add is often a combination of all these factors.

How does one go about capturing the total value add? In our experience, it’s a three-step process:

- Diagram all the incremental sources of revenue increases and cost savings in a fishbone-type, cause and effect diagram

- Either as a thought exercise or to create the beginnings of an ROI tool, quantify the revenue increases and cost savings

- Extract qualitative statements of where and how “value is accrued,” i.e., revenues increased, or costs saved, and synthesize the results into an overall, verbal framing of value adds

Diagram all the Incremental Sources of Revenue Increases and Cost Savings

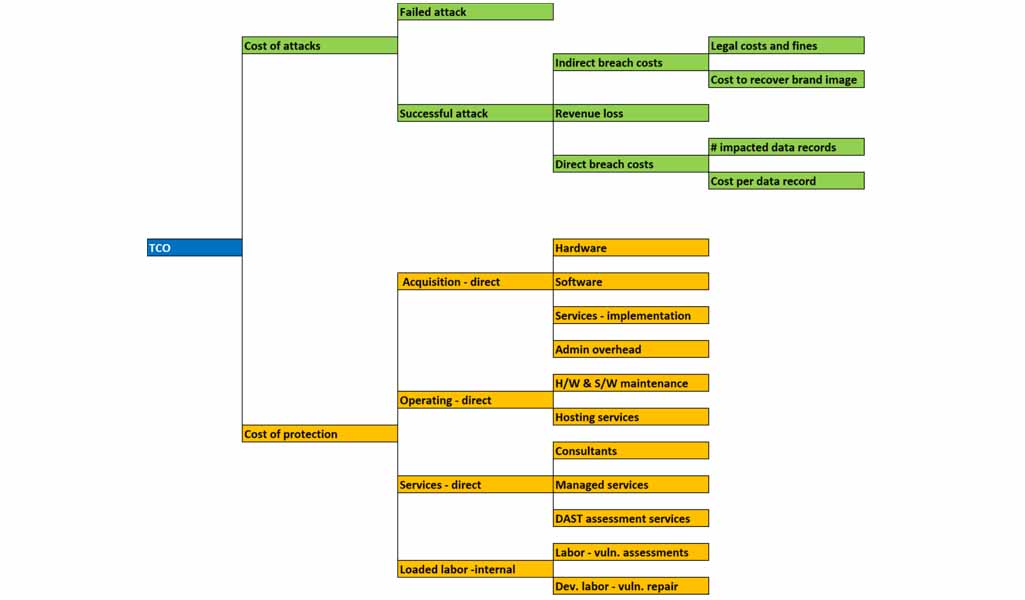

This is an accounting-based breakdown of the buyer’s costs and revenue sources, kind of like creating a faux P&L for the buyer. Then combine that with an assessment of which of the origins of revenue growth and cost savings could be impacted by the implementation and use of your offering. An example of such a diagram, taken from the world of cybersecurity, is shown here:

Quantify the Revenue Increases and Cost Savings

Once a layout like the above has been built, and we suggest using a spreadsheet because it makes this next step more manageable. Each node in the diagram can be associated with the higher-level nodes through a series of arithmetic relationships, aka formulas. For example, if revenue is volume times price, then the spreadsheet can be modified by capturing the associated method, as well as the needed coefficients such as unit prices or costs.

Key to ensuring the resulting value calculations don’t double-count savings or miss entire categories of benefits, the nodes at any one level in the diagram need to be “mutually exclusive” (i.e., don’t overlap) and “cumulative exhaustive” relative to the next higher node (i.e., capture elements contained in a higher node completely). The acronym for this analytical scrutiny is called “MECE.” It ensures the cost and revenue calculations that sum up to a higher level node are complete and don’t duplicate effects.

Extract Qualitative Statements of Where and How “Value is Accrued”

Once the above analytical framework has been built, but you don’t want to take it to an ROI tool, say, then it’s still useful to translate the framework into its qualitative components. For example, for one of our security clients, it became clear that their technology did not reduce the risks of an attack (their prior messaging). Still, it reduced the size of the ultimate damages from an attack, as well as the total costs of preventing attacks because their product allowed for more efficient deployment of the security infrastructure. The resulting messaging then was all about controlling financial exposure, and not about risk reduction, as it had been before with limited success.

This analytical and replicable approach helps you create a marketing message that crisply expresses your sources of value add, and thus lays down the analytical foundation for more effectively differentiating your company’s product and services. Once you have formulated your value propositions, they can then be exported to positioning statements and messaging pillars, and become the defensible and compelling underpinning of your company’s messaging framework.